Nicky Sherwood: A visit to the Fitzwilliam Museum to see Woolf's manuscript

Participant Nicky Sherwood writes about one of the visits made during the Woolf’s Women summer course 2023, Cambridge

On an unseasonably drizzly Thursday in July, all the students from the Woolf’s Women Summer Course were invited into the calm sanctuary of the Fitzwilliam Museum for a private viewing of the manuscript of Virginia Woolf’s influential essay A Room of One’s Own.

Woolf had given two talks in October 1928 at Newnham and Girton Colleges entitled ‘Women and Fiction’ in which she famously proposed that, in order to write fiction, women needed an annual income of £500 and a room of their own in which to work. These talks formed the basis for the essay A Room of One’s Own which was published by the Hogarth Press the following year in 1929. A year after Woolf’s death in 1941, her husband Leonard donated a manuscript entitled ‘Women and Fiction’ to the Fitzwilliam Museum, along with a letter explaining that it was in fact the first draft of A Room of One’s Own.

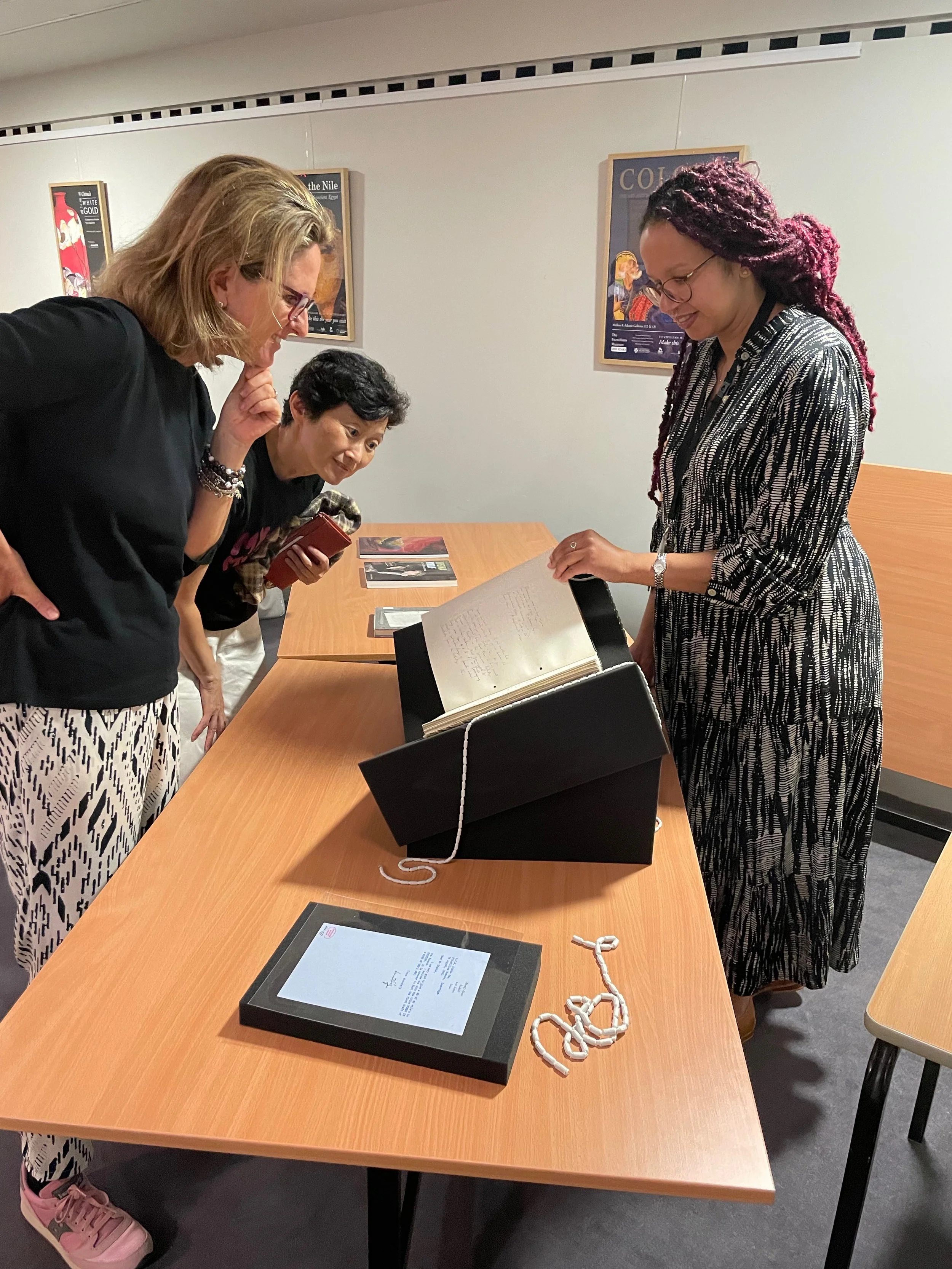

Dr Mathelinda Nabugodi shows participants the ms of A Room of One’s Own

In the low light of the archive room beneath the museum, we gathered in hushed anticipation as we were introduced to the work by Fitzwilliam Museum Research Fellow Dr Mathelinda Nabugodi. The open manuscript sat tantalisingly on a table in the corner, carefully removed from its custom-bound archive box. An orderly line formed as the students were invited to step forward in pairs to view the iconic words on the page.

The first thing that struck me about the manuscript was not so much the content but the sheer physicality of the writing. You can almost see the author hunched over the loose leaves, hear the scratch of the ink-filled nib as it flies across the paper. The manuscript was written quickly, while Woolf was recovering from an illness. In her diary she describes the words as ‘pouring out’ like water from an upturned bottle as ‘the thinking had been done’. The lines of purple-blue handwriting start off parallel then gradually begin to slant upwards, seeming almost ready to take-off by the time they reach the bottom of the page. You can imagine the angle of the author’s arm, wrist, elbow, the hunch of the shoulders, perhaps a tilt of the head and neck, or the jut of the chin. Were the lips pursed, the jaw clenched, the tongue pressed hard against the teeth?

There is an essence of speed – not careless but not precious either – jotted down as the thoughts came into the author’s mind. A kind of thinking out loud, or even a stream of consciousness. You can see the fluidity of thought as the words take shape on the page, the thought process organic and evolving. Woolf was not afraid to put pen to paper, unafraid to make a mark on the page and then amend it. There are revisions, additions, scratched-out words. This is clearly a work in progress, evolving from the mind of the author.

On some pages, words are crossed out with a deft swipe, while larger sections are erased with a fluid undulating wave or a gracious arc reaching across an entire paragraph. Occasionally single letters are deleted with a clockwise spiral. Some revisions take the form of single words in the wide left-hand margin, while larger amendments or additions are written loosely across the left-hand page. Not a novel this time, but a thought process, a conversation, a lecture, an imagining of past and future intertwined. But most of all, a real person – the handwriting forming a self-portrait of sorts.

Seeing Woolf’s handwriting on the page was like the difference between looking at a painting printed in a book versus the original artwork with its brushstrokes and texture, worked and reworked until complete in the eye of the artist.

I was taken aback by the sheer presence of the hand-written words compared to the more familiar typed format. There was no backspace button, no ‘undo’ command – we get an insight into the author’s thought process in a way that wouldn’t be possible today. A typeset book democratises the content, reducing it to a common denominator, but this handwritten manuscript shows humanity, personality, character, flaws, mistakes, misgivings, questions.

Outside the Fitzwilliam, July 2023

We know that Woolf wrote and rewrote obsessively, returning to her works many times, sometimes over a period of decades. We know that she often experienced periods of ill-health after finishing a book, as if she had poured all of her creative energy onto the page and was left depleted, physically and mentally. It is here in the loops and descenders of the handwritten words, that we can imagine the physical body behind the brain, the person with all of her brilliance, frailty and humanity.

This manuscript is not just a collection of words by one of the greatest writers of the twentieth century, it’s a living breathing signature written over 134 pages.

Nicky Sherwood

London, UK

The next Virginia Woolf summer course in Cambridge takes place 5-9 August 2024.

You can view the whole of the manuscript on the Fitzwilliam Museum website here.