The Waves at the ADC Theatre

Suzanne Présumey reviews the latest adaptation of Virginia Woolf’s The Waves, written and directed by Sarah Taylor and performed at the ADC Theatre, February 2020.

*

In 1933, Virginia Woolf wrote about seeing a performance of Twelfth Night at the Old Vic:

And then by degrees this same body or rather all these bodies together, take our play and remodel it between them. The play gains immensely in robustness, in solidity. The printed word is changed out of all recognition when it is heard by other people. […] Perhaps the most impressive effect in the play is achieved by the long pause which Sebastian and Viola make as they stand looking at each other in a silent ecstasy of recognition. The reader’s eye may have slipped over that moment entirely. Here we are made to pause and think about it […][1]

Sarah Taylor’s adaptation of The Waves conveys robustness and solidity, not only inasmuch as it adapts Virginia Woolf’s 1931 novel (or prose poem) by staying very close to the written words, but because it does not take the route of abstraction and arcaneness as previous adaptations have tended to. Indeed, as Gillian Beer pointed out during intermission, the most famous theatrical adaptation prior to this one, Katie Mitchell’s 2006 waves, adopted a much more Brechtian approach, surrounding the characters with machines and technology, whereas this 2020 adaptation is staged on a simpler set. At the beginning, the stage is empty except for a raised platform acting as a stage on the stage.

But there is nothing severe or remote about this production; the actors immediately bring in life when they enter as the children Rhoda, Louis, Susan, Bernard, Neville and Jinny. Their energy soon conquers the space, and as the play goes on the six actors themselves set up a variety of props and set pieces that represent the different stages of their characters’ lives, including a large table around which they gather for the most remarkable ensemble scenes. Videographer Olivia Railton’s clips of landscapes are projected on a canvas that comes down to conceal the stage at points that correspond to the parts of the novel Woolf wrote in italics as interludes, and are accompanied by musical arrangements that evolve from light piano notes to more ominous bass tones as the characters age.

As cast member Ben Phillips (Neville) pointed out in the program notes, this play is an opportunity for the young actors, all students and members of the Cambridge University Amateur Dramatic Club, to perform different ages and stages of life in one night. His portrayal of Neville is skilful in maintaining a sense of vulnerability that would have perhaps been more obvious in Louis, a character plagued by embarrassment over his Australian accent, as Tom Foreman’s lines frequently remind us to the audience’s hilarity. While it could appear that their character is the one in the novel who undergoes the least change, Amelia Hills is able to convey Rhoda’s uniqueness and tendency to stray from the norms that the other characters follow or feel compelled to adhere to. Their emphasis on Rhoda’s insecurities and propensity for doubt comes through in a subtle gestural language, as well as in the costumes choices that highlight the difficulty of fitting in. The work of costume designer Caroline Katzvie deserves to be appreciated from the front row, where one can see better a hole in Neville’s sock that recalls his aforementioned vulnerability, or the fine embroidery on Susan’s dress as she has become a mother that echoes the work on shapes and colour of interior designer Vanessa Bell, Virginia Woolf’s sister.[2]

However, both Alice Murray’s portrayal of Susan and the play as a whole avoid a frequent pitfall of adaptations of Woolf’s writings: none of the connections between the fiction and the author’s life are made too obvious or weighty. The ambiguity of what real person or relationship may or may not be alluded to is fully preserved, as well as the potential for the characters’ fleeting, changing and queer attractions. If any form of faithfulness were to matter to the adaptation of this text, it was precisely the adherence to its resistance to definitions and boundaries. The ensemble scenes around the oval-shaped table in particular are proof of Taylor and the cast’s awareness of the importance of keeping these characters on an equal footing, letting them express their every thought without judgement, while depicting each other’s reactions. What we might call the ‘eye acting’, both through directing the gaze and deciding when to blink or raise one’s eyebrows, of each actor while another one is monologuing, allows for many interpretations of each scene. While such variety was already present in the novel, the simultaneity allowed by theatre offers a tremendous opportunity for sentimentality, and more often than not, laughter. The challenge is met particularly brilliantly by Orli Vogt-Vincent as Jinny, whose eye movements are described by the others as she performs, but the entire cast makes good use of it as well as diction to create what many would not have expected from The Waves: fun!

The six characters in The Waves as children. Photo credit: Alessia Mavakala

The Waves is a very witty, at times hilariously reflexive text that allows flaws to become endearing. It is also a portrait of middle-class Englishness, from countryside to London life, as the simple props used reflect, from the sculptural wood pieces of furniture to ornate bouquets and kettles. Material details that might have been lost in the novel’s flow of descriptions and sensations are singled out to brilliant dramatic effect, particularly when it comes to Neville and Bernard having tea and the subsequent use of cups to point to the growing distance, and yet consistent affection that exists between them.

Lisa Hutchins’ remarks on reading The Waves out loud,[3] as was done during a recent 12-hour marathon for a Literature Cambridge Study Day, point to the importance of engaging with the novel as spoken voices. As Woolf suggested about the performance of Twelfth Night, bringing the text to the stage allows us to perceive moments that ‘the reader’s eye may have slipped over’ by using pauses. In this performance, however, it is also sometimes not pausing, or changing intonation to hurry a line, that allows for humour and liveliness. The line, attributed here to Louis, about ‘a little language such as lovers use, words of one syllable such as children speak’, reminds us of the materiality of language, and echoes the famous recording of Woolf on the BBC,[4] which starts: ‘Words, English words, are full of echoes, of memories, of associations.’ This staging of The Waves fully uses its cast of six to materialise these echoes.

While Woolf’s text is not considered a play, it is, in her own words, a hybrid between ‘a novel and a play’.[5] Taylor’s adaptation takes advantage of the text’s theatrical features, particularly its last line, ‘The waves broke on the shore.’[6] In the novel, the fact that it is written in italics and incorporated in the main text (contrarily to the interludes which are in italics but separated in their own sections) makes it appear as stage directions. Stage directions that may now be perceived to apply to us, the audience. How beautiful a moment of this 2020 mise en scène it is, when the soundtrack of crashing waves used as conclusion is covered by exhilarated applause, signalling the end of the performance, and the sound of waves is turned into an even louder roar, as if one had stepped a little bit closer to where land and sea meet.

Suzanne Présumey, King’s College London

________________________

[1] ‘Twelfth Night at the Old Vic’, in Virginia Woolf, Collected Essays (New York: Harcourt, Brace & World, 1967).

[2] The explanatory notes to the Cambridge edition of The Waves suggest: ‘Susan may contain elements of Vanessa Bell, who was Virginia Woolf’s closest contemporary with experience of motherhood.’

[3] https://www.literaturecambridge.co.uk/news/hutchins

[4] ‘Craftsmanship’, BBC Broadcast, 20 April 1937.

[5] Virginia Woolf, The Diary of Virginia Woolf, vol. 3, ed Anne Olivier Bell and Andrew McNeillie (London: Hogarth Press, 1980).

[6] Virginia Woolf, The Waves (1931), ed. Michael Herbert and Susan Sellers (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2011).

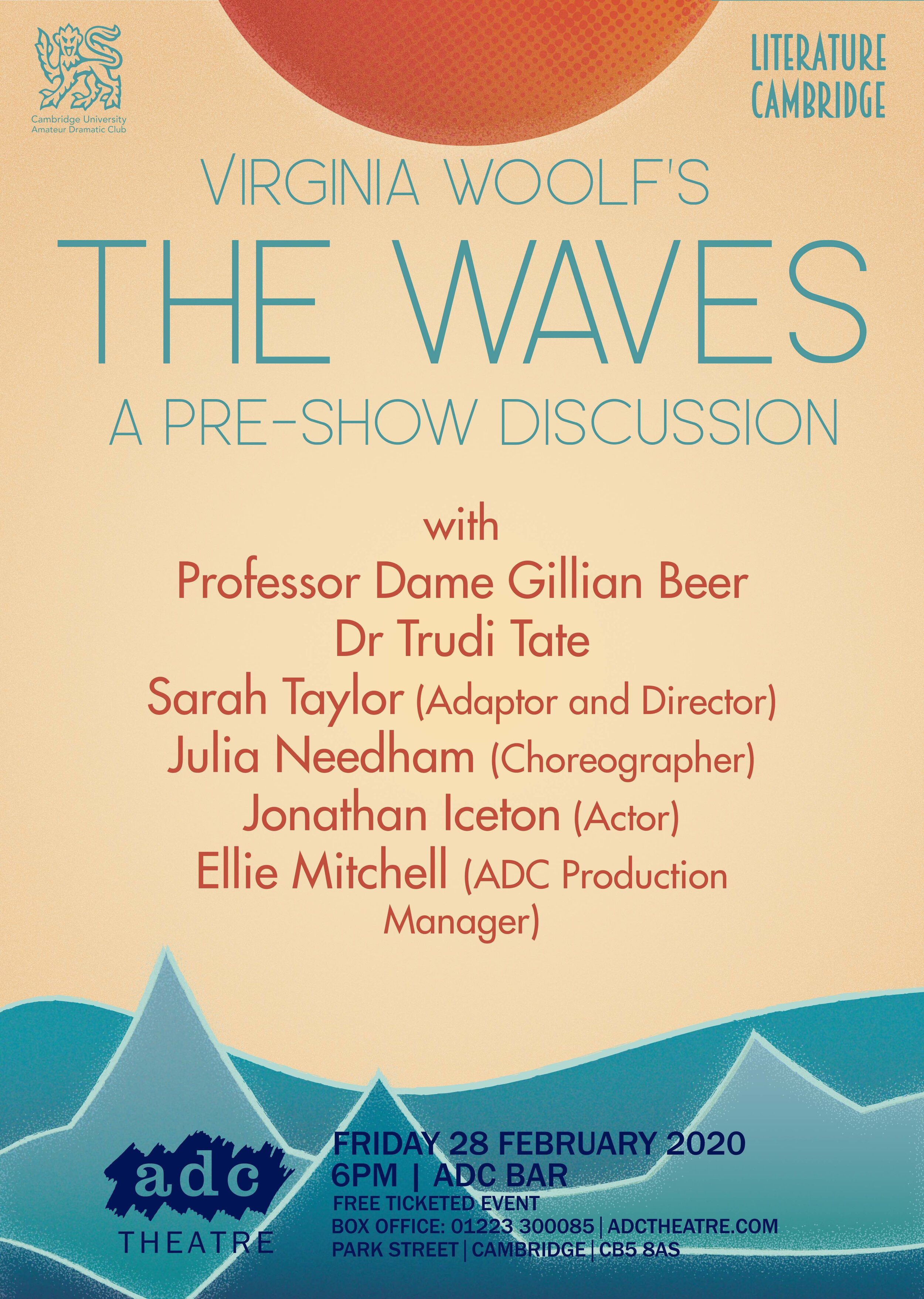

Panel discussion

On Friday 28 February 2020, the performance was preceded by a panel discussion chaired by ADC Theatre Production Manager Ellie Mitchell. Professor Dame Gillian Beer, retired King Edward VII Professor of English at Cambridge, described the different stages and drafts that led to the writing of The Waves. She provided valuable background about the challenges Woolf faced when trying to portray characters of different socio-economical backgrounds. Dr Trudi Tate, director of Literature Cambridge, talked about ways in which The Waves speaks to readers at different stages of our lives. Adapter Sarah Taylor gave fascinating insights into the process of adapting the play. Originally she considered turning it into a dance performance. Movement remains important in the play, and choreographer Julia Needham talked about the use of movement to convey emotion. Actor Jonathan Iceton talked about playing the character of Bernard (a role he played quite wonderfully).

Link: Adapting The Waves for the stage: ADC theatre website.