Adrian Poole: Shakespeare, Tragedy and Rome

From ‘Shakespeare, Tragedy and Rome’ lecture, 18 March 2017

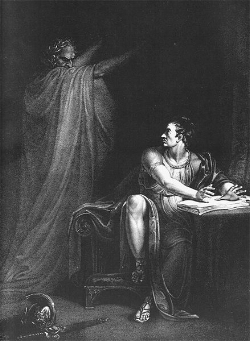

‘Lord, what fools these mortals be!’ exclaims Puck, in A Midsummer Night’s Dream. A comedy, to be sure, in which nobody dies, no blood gets spilt. But that is indeed one perspective that tragedy offers – one of apparently god-like immunity from which we can look down with horror or amusement or both on those ignorant and benighted mortals, who can’t foresee their own doom. But it’s not the only one. There is another perspective, essential to tragedy, especially in the conditions of live performance, in which we share the same space and time as the actors playing these benighted mortals, and are drawn to experience their pain, their hope, their living and dying in the present, or what Iago calls ‘now, now, very now’. The moment when things could still be otherwise; when Medea might choose not to kill her children; when Brutus might decide not to join the conspirators, when Caesar might listen to Calpurnia and not go to the Forum.

*

Here’s what makes Shakespeare’s Roman plays speak to us, and our world. Is it really or solely for the good of Rome that its citizens risk their lives? Or is it for something more personal, their own glory, their own name and fame? There’s no problem of course when the two coincide, as they do for Caius Martius on the battle-field against the Volscians, where he fights so bravely from Rome and himself, winning honour and glory for both at once. What happens however when he returns home to Rome, and moves ‘from the casque to the cushion’ (as Aufidius puts it)? And what happens when Romans disagree about what they are fighting for and start fighting amongst themselves? What happens when their vision of Rome and what it means to be Roman radically differs? What happens when these ideals melt away and we are left with a brute struggle for power, with more or less naked self-interest, masked by shameless political rhetoric and the appeal to ‘the people’s’ self-interest? What happens is civil war, and the degeneration of political values and ideals to the great game of grab (a memorable phrase of Henry James’s). I won’t insult your intelligence by making explicit the parallels with our own world today, on both sides of the Atlantic, that Shakespeare’s Roman plays are bound to provoke.

Adrian Poole

Trinity College, Cambridge